In this fourth installment of our “Lost Legends” series, delve into the history of the Chicago and North Western Station in West Loop Gate. This Italian Renaissance Revival-style structure was once an architectural icon in the heart of the city. Originally designed by architects Frost and Granger, the station stood proudly from its inauguration in 1911 until its demolition in 1984 to make way for the Citicorp Center Tower.

The Beginning

The Chicago and North Western Station. Photo from Lost Chicago by John Paulett and Judy Floodstrand, Pavilion Books, 2021.

The inception of the Chicago and North Western Station traces back to the establishment of the Galena and Chicago Union, which built the Wells Street Station in 1848. After merging with the Chicago and North Western Railway in 1864, the combined entity continued to operate out of Wells Street in The Loop. The original station was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1871, leading to the construction of a temporary wooden replacement and ultimately a more permanent Victorian edifice that stood from 1881 until 1911.

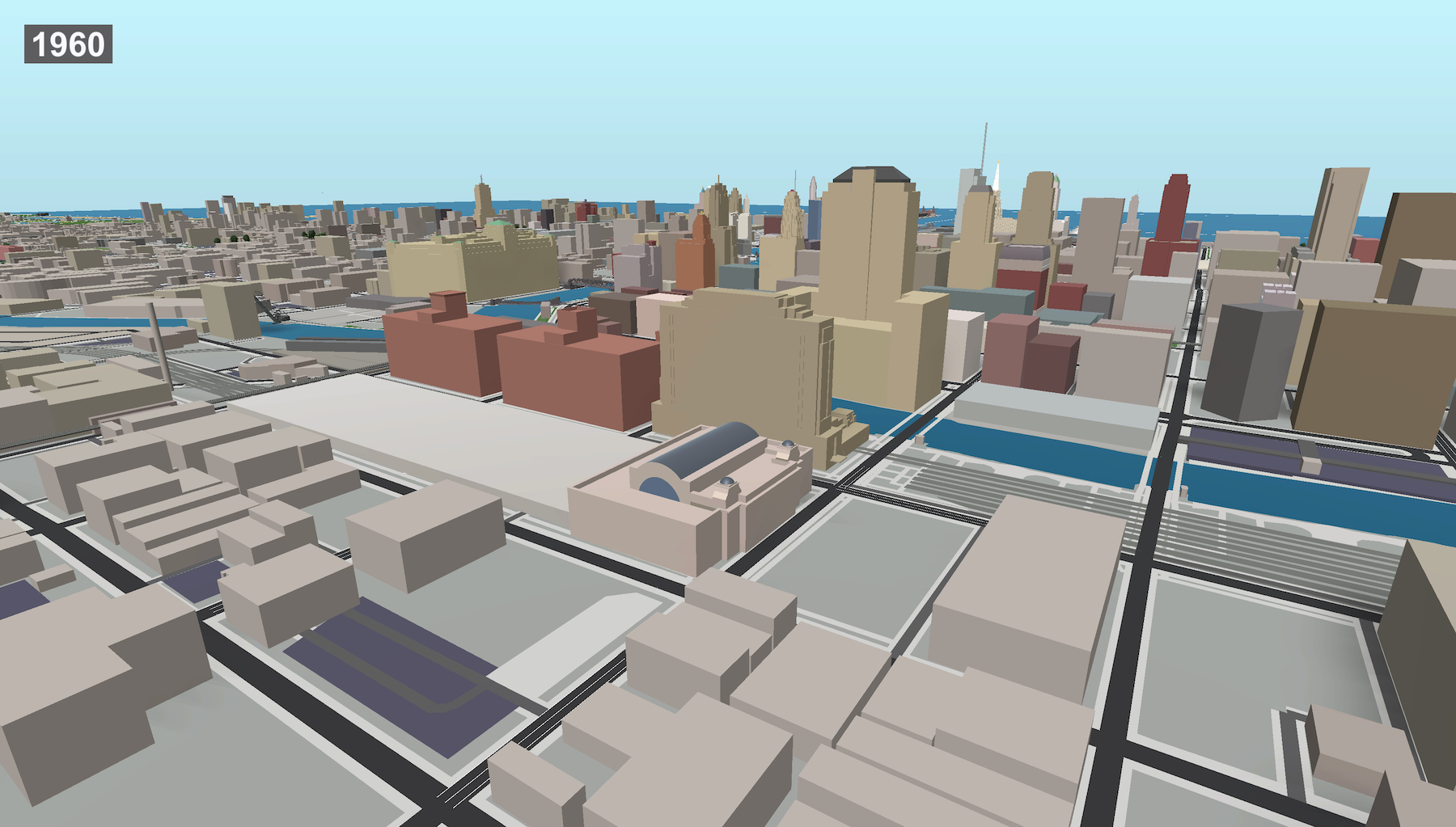

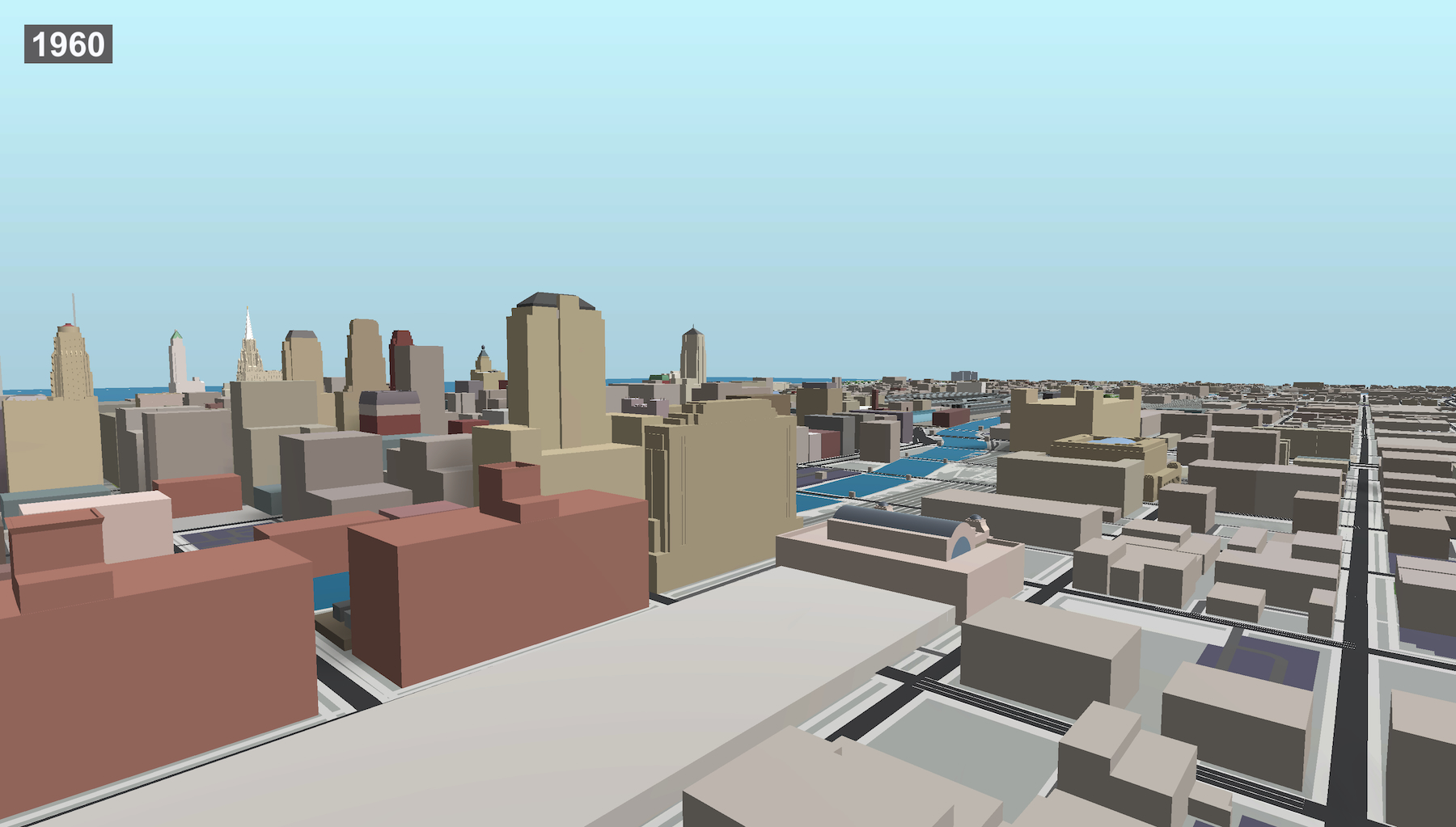

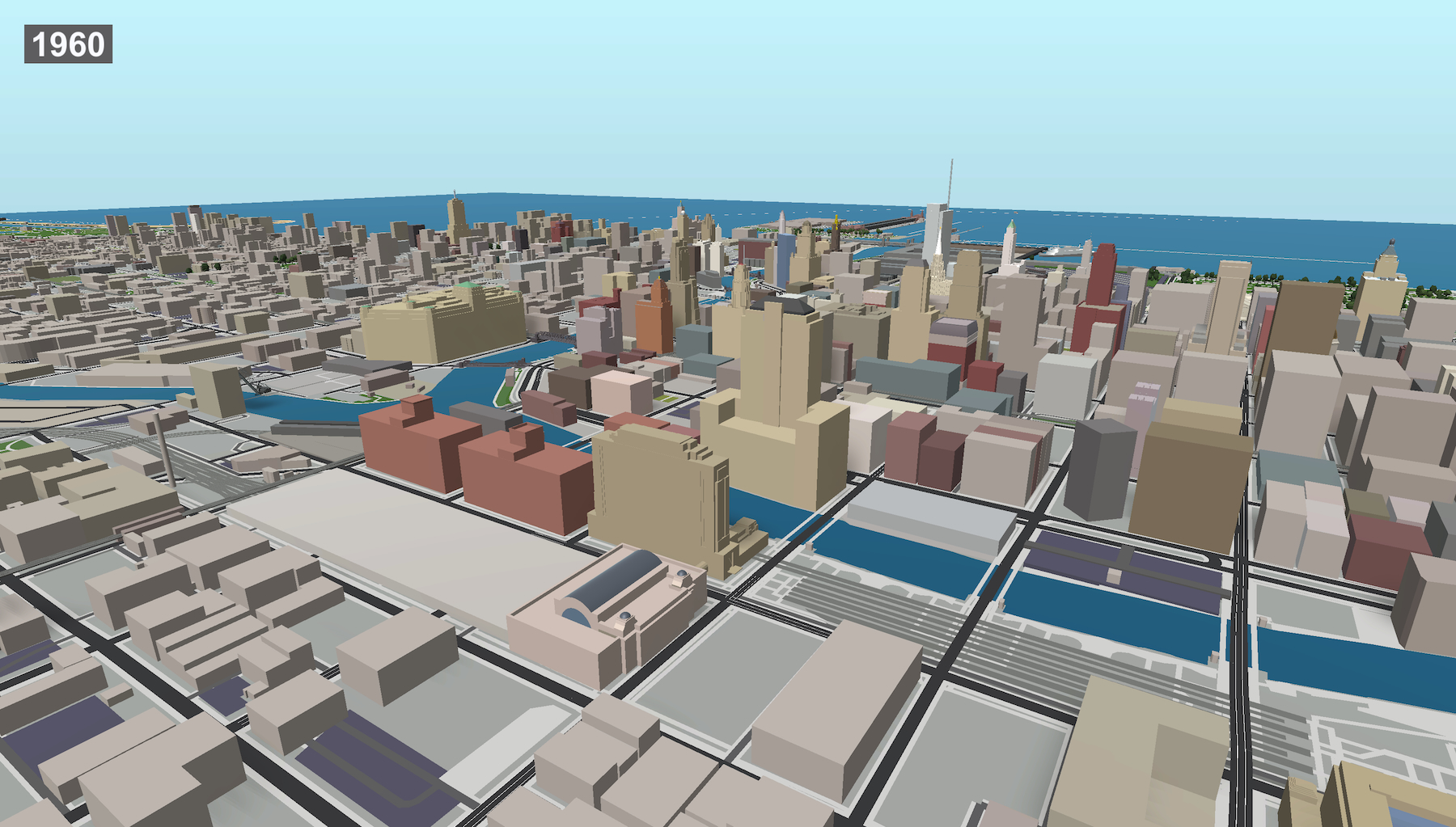

Chicago and North Western Station in 1960. Model by Jack Crawford / Rebar Radar

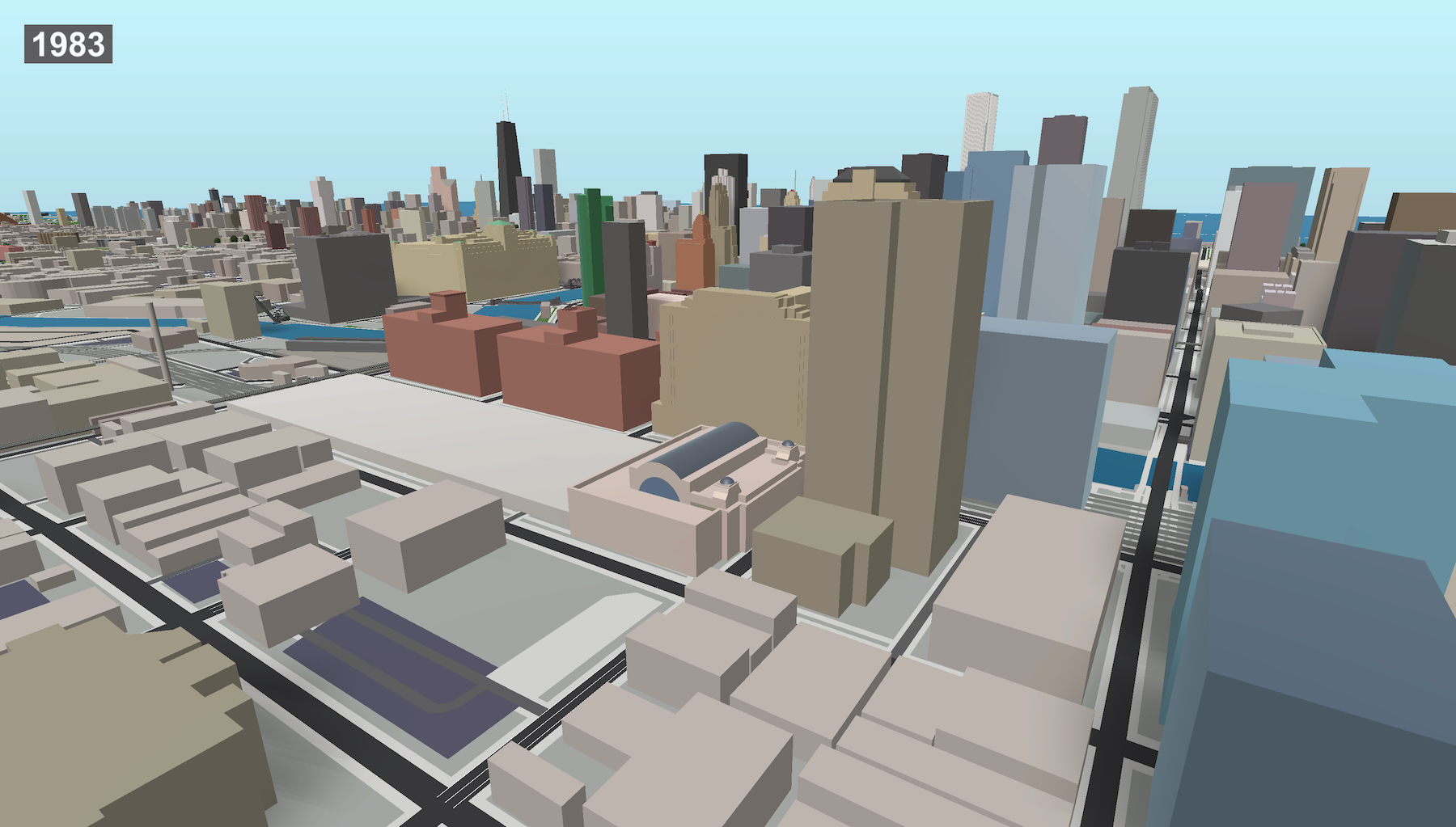

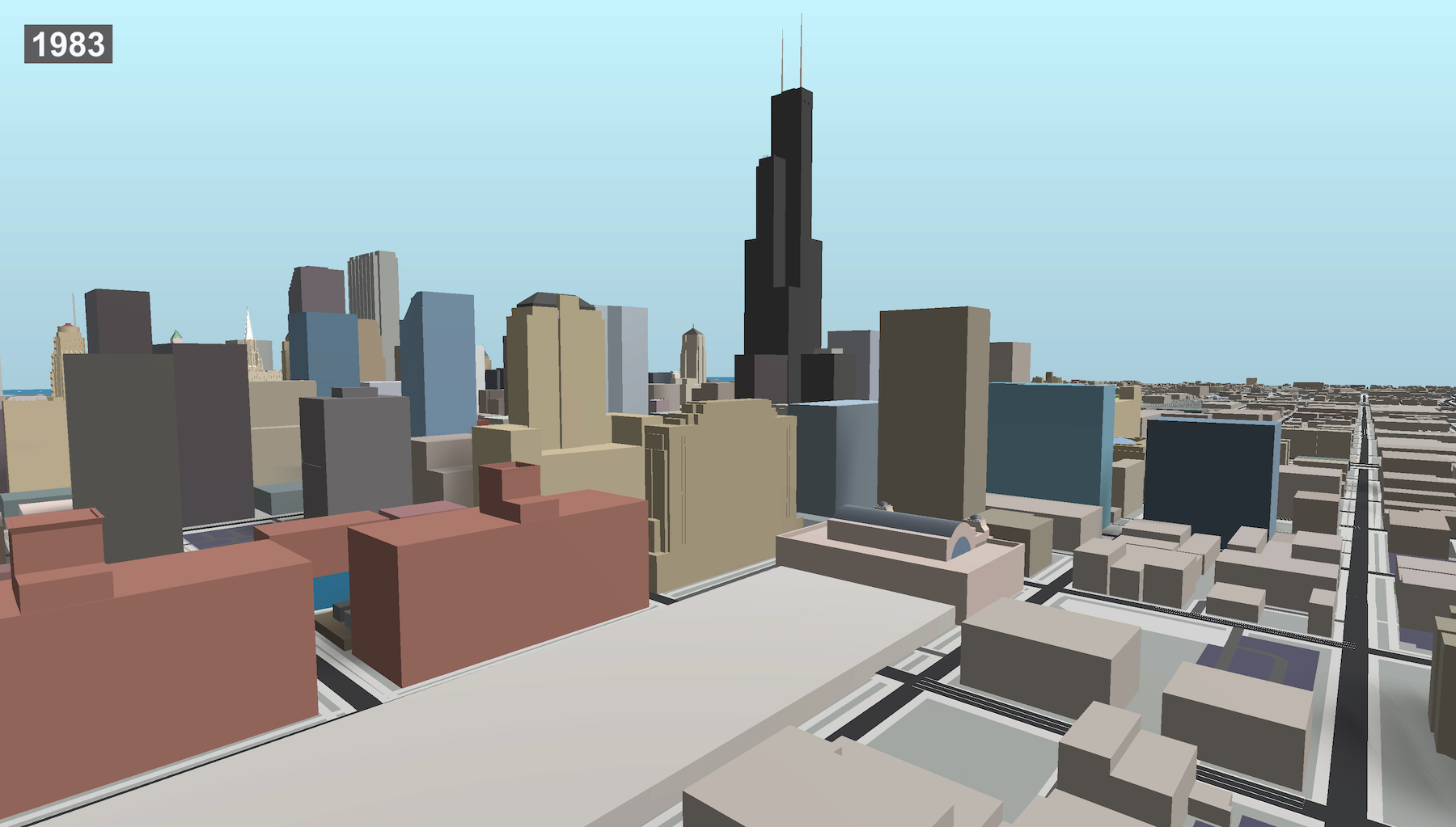

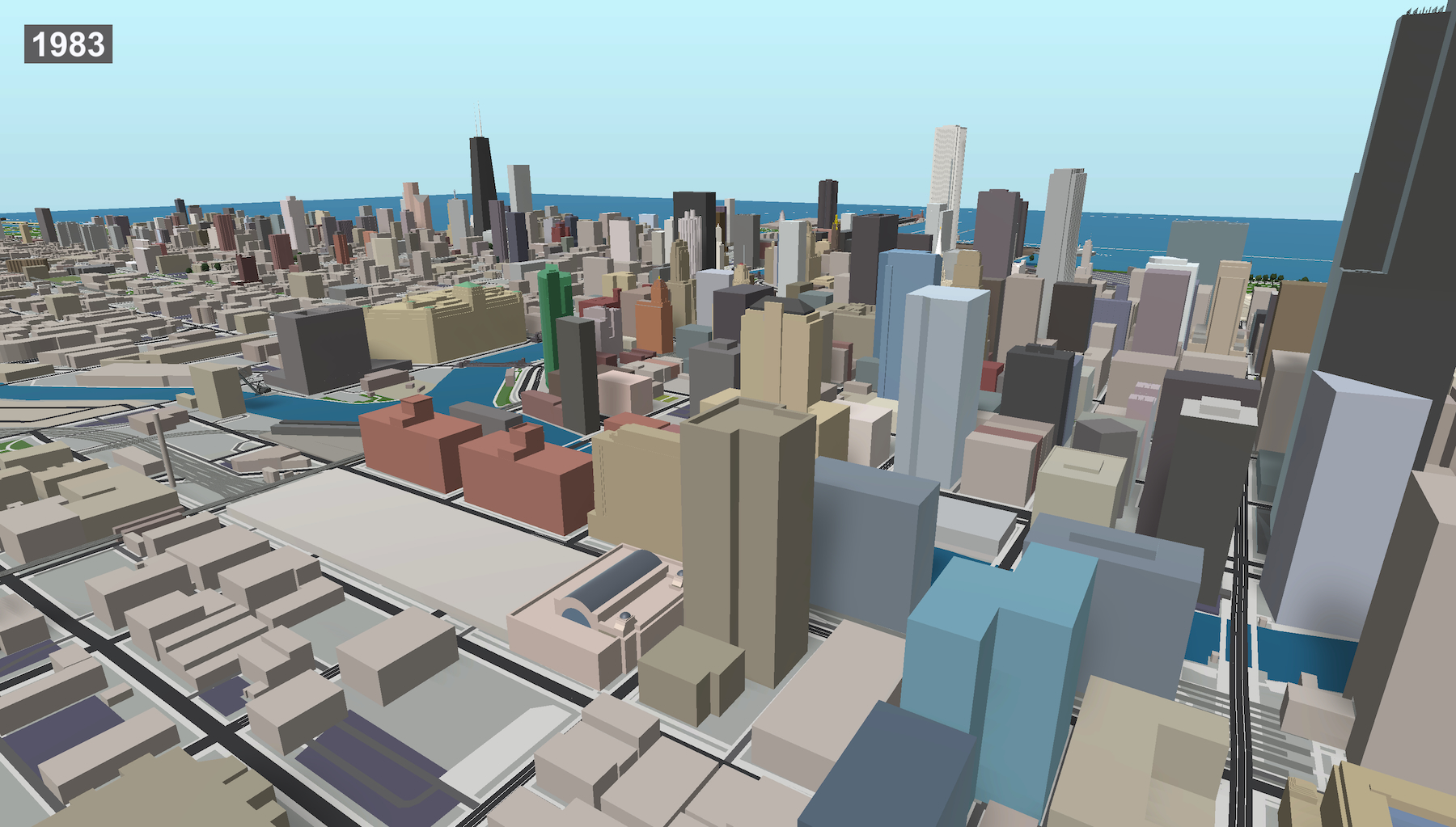

Chicago and North Western Station in 1983, one year prior to demolition. Model by Jack Crawford / Rebar Radar

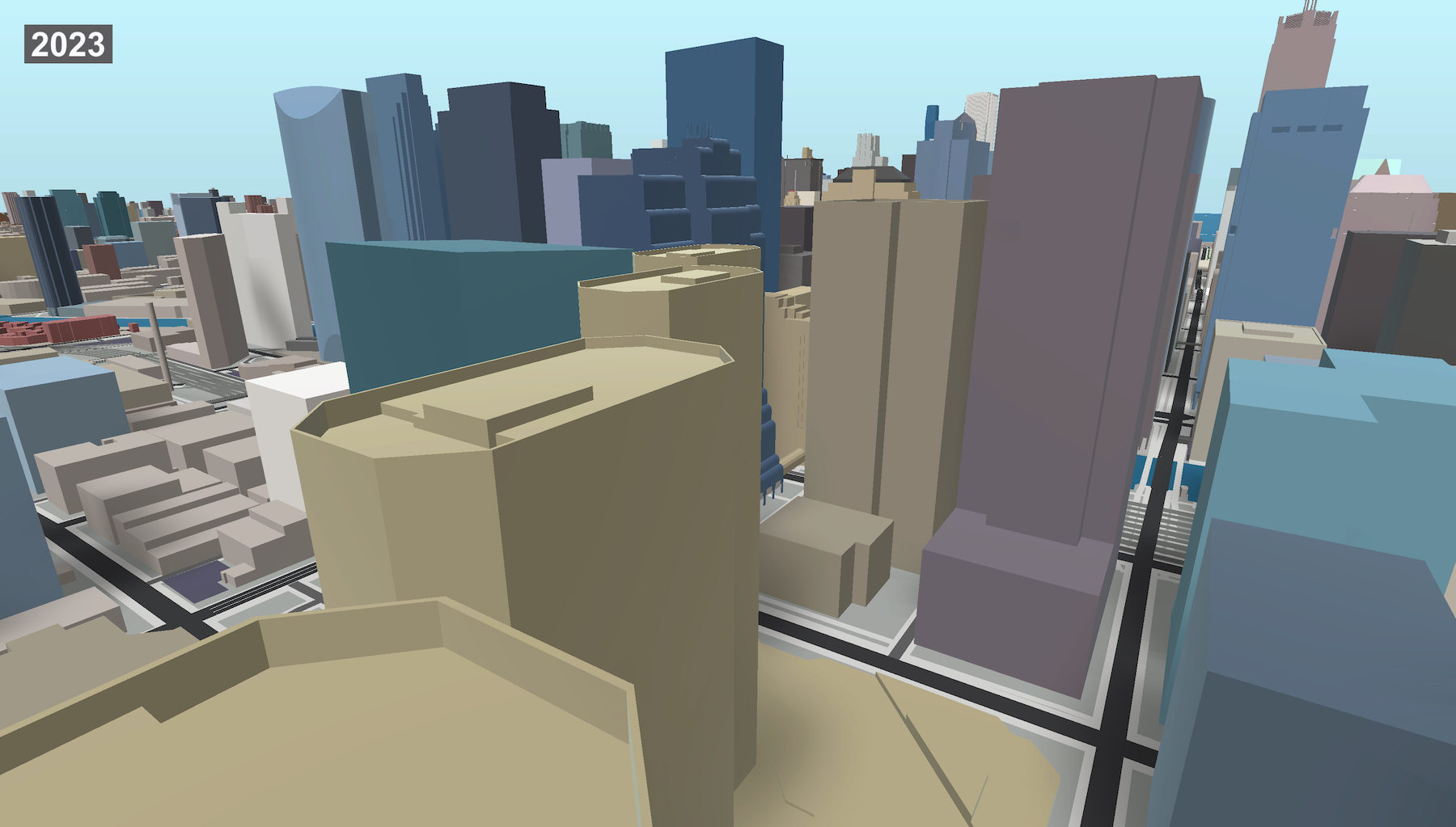

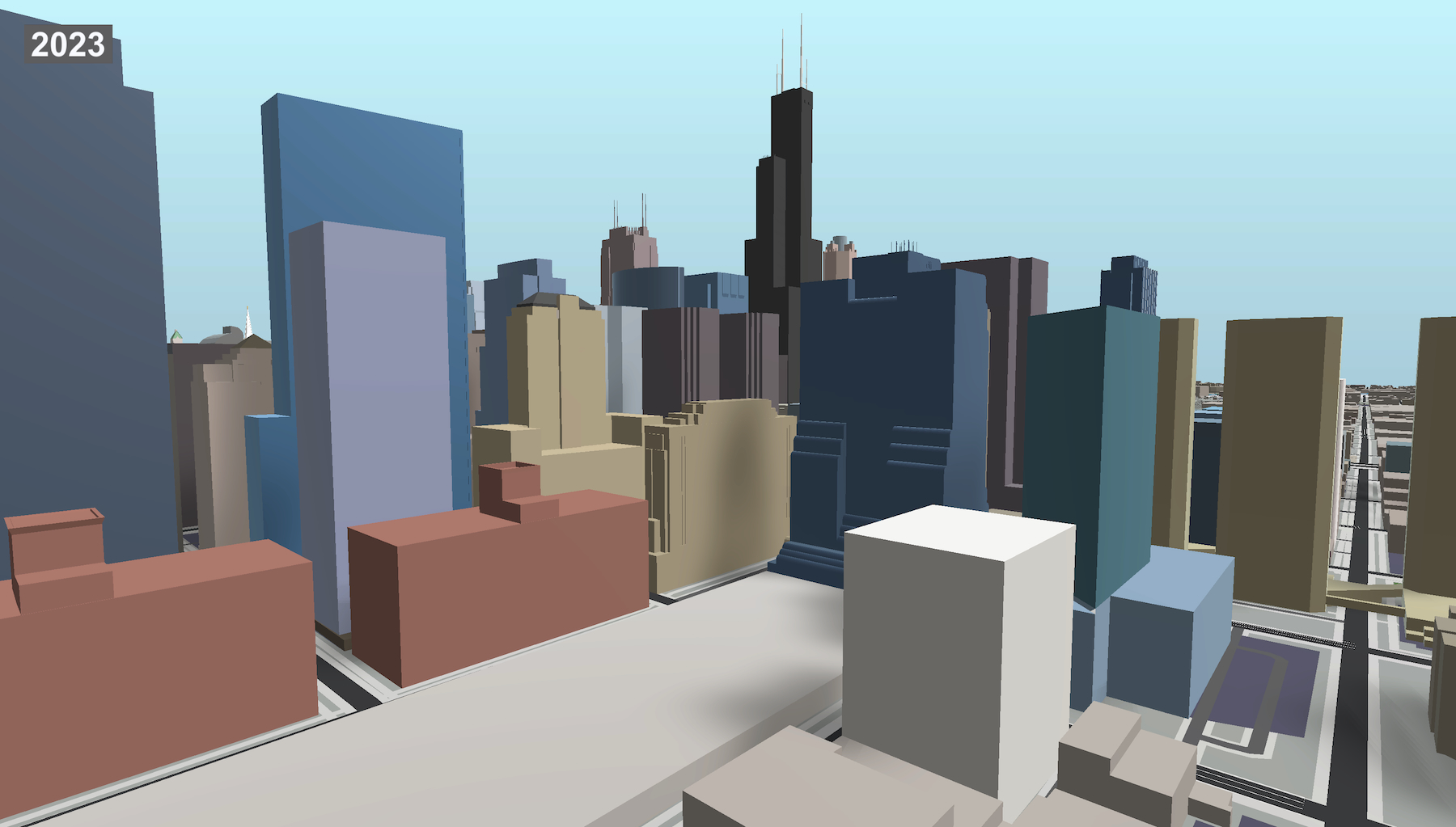

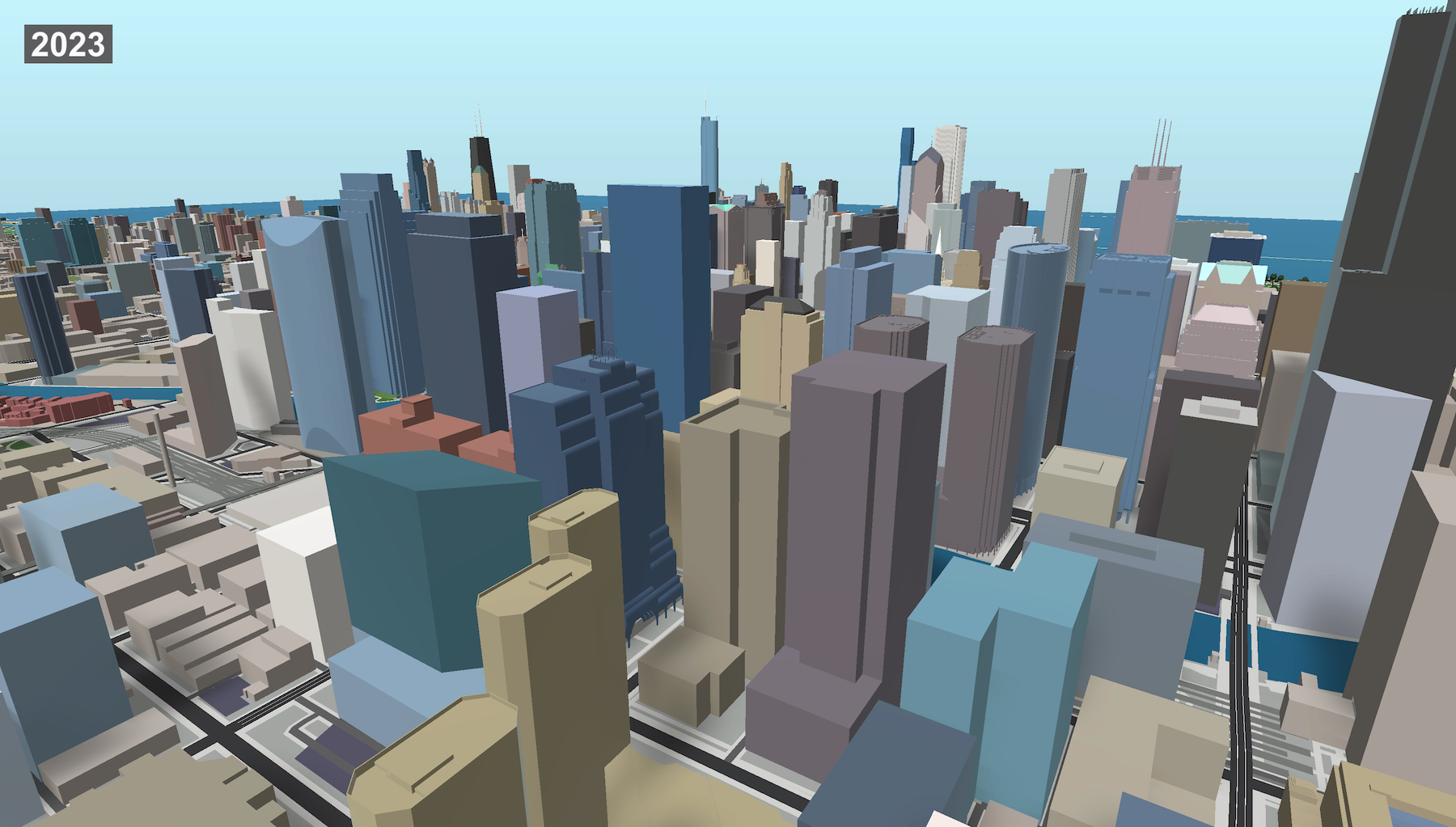

View of where Chicago and North Western Station once stood in 2023, 39 years after demolition. Model by Jack Crawford / Rebar Radar

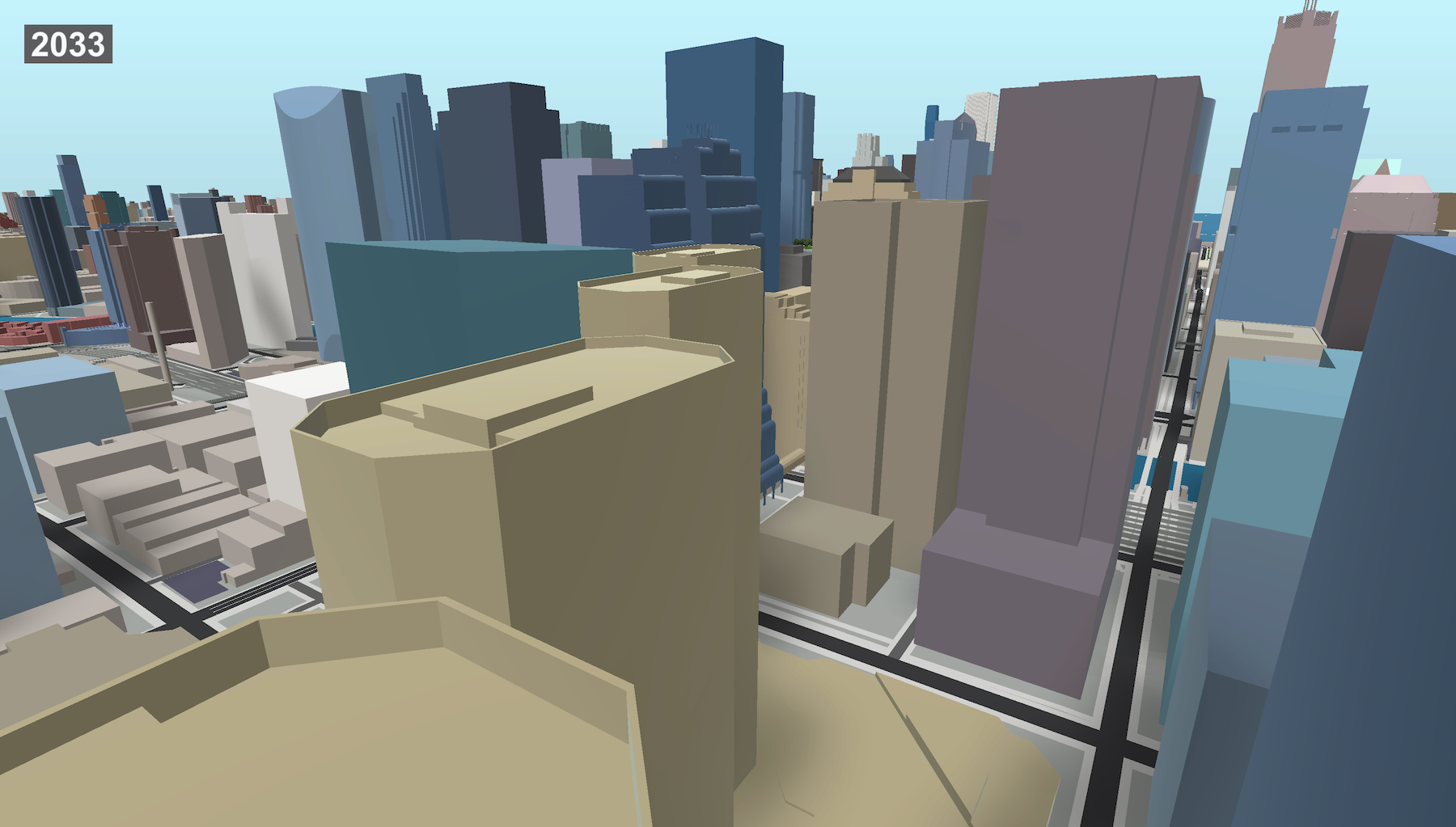

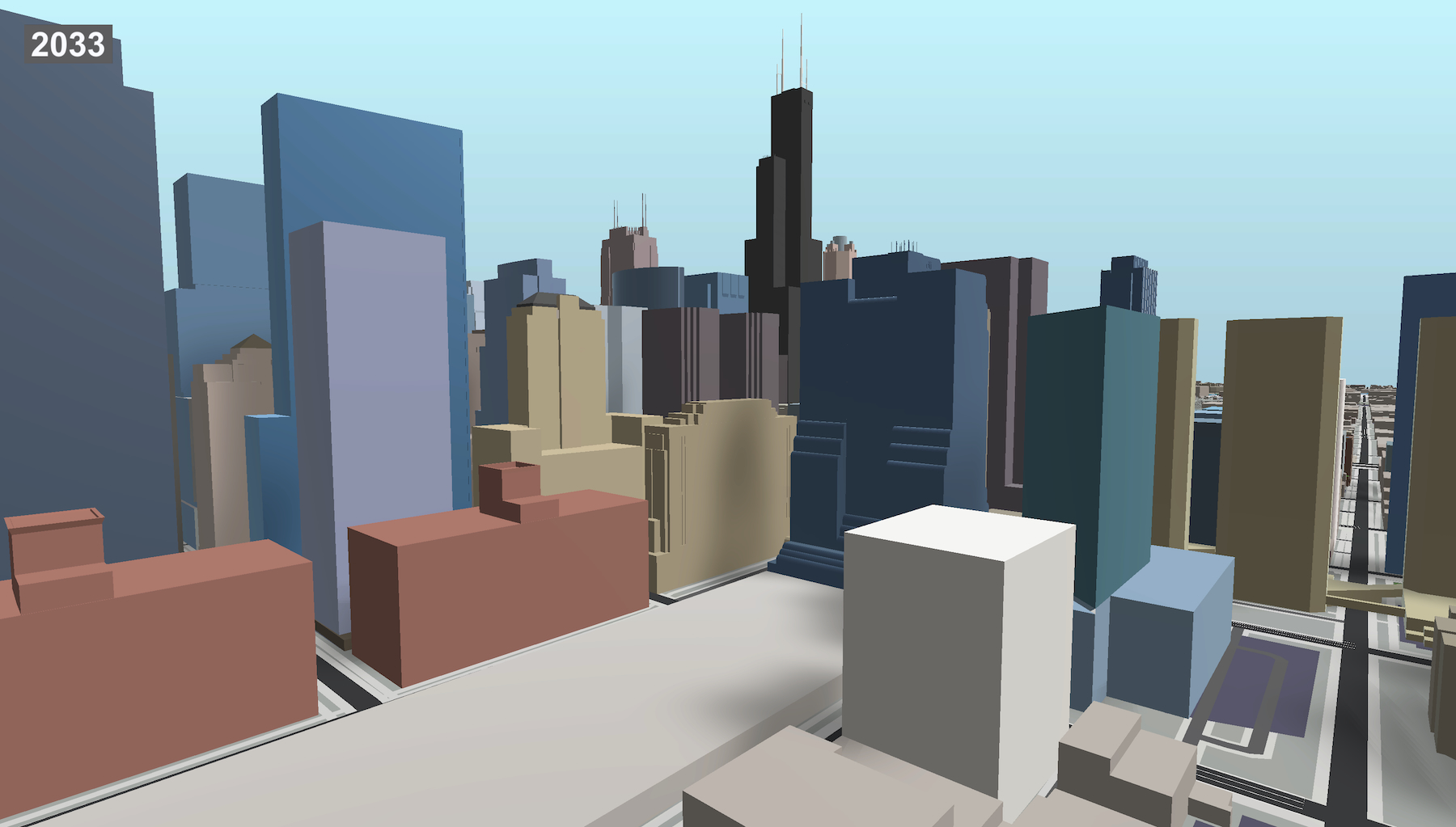

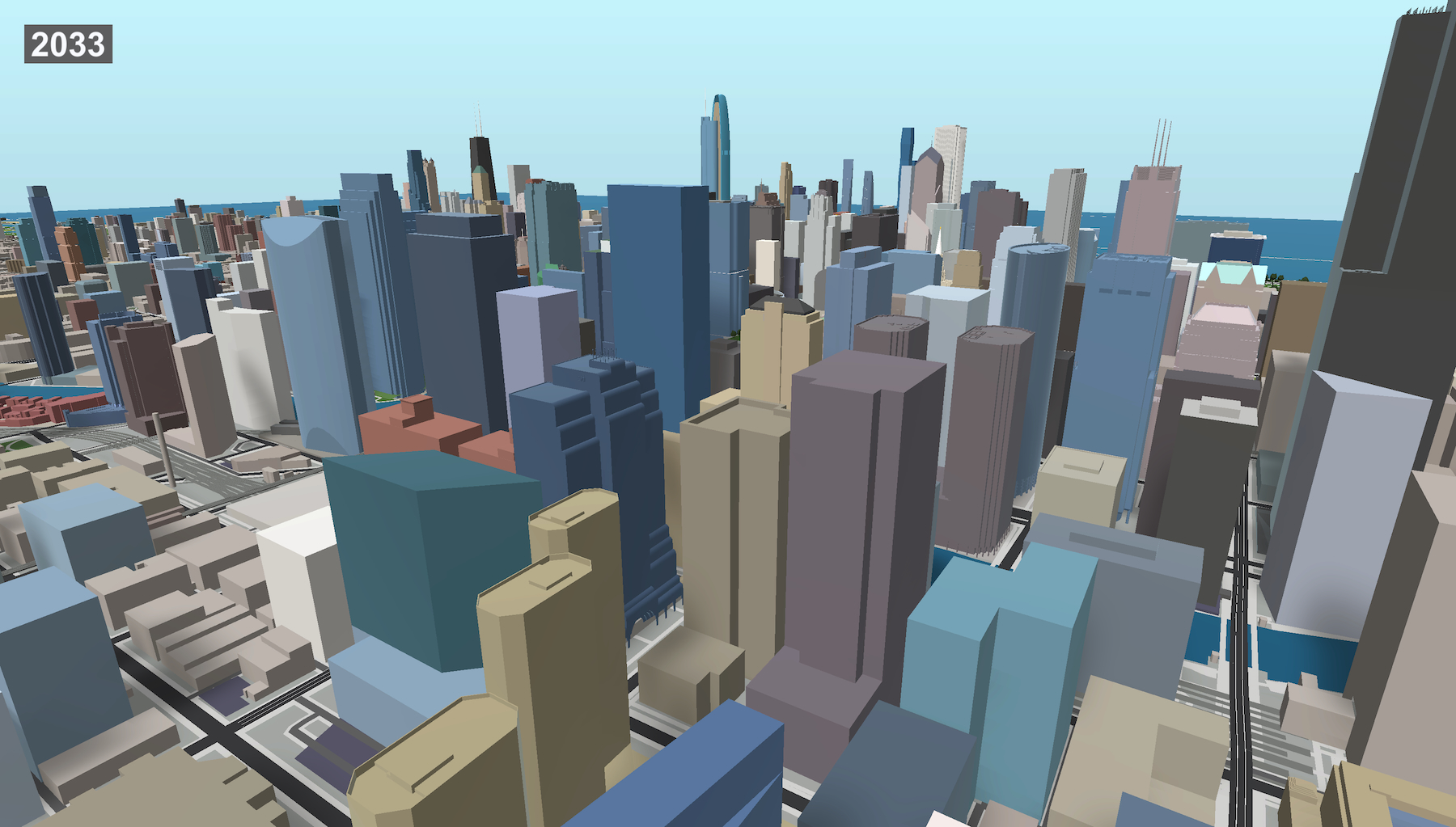

View of where Chicago and North Western Station once stood in 2033, 49 years after demolition. Model by Jack Crawford / Rebar Radar

To adapt to evolving traffic patterns, elevated approaches were added to the Chicago and North Western Station, prompting a relocation of operations across the Chicago River in 1911. The grand station comprised 16 elevated tracks, all situated above street level, with six approach tracks guiding passengers into the 894-foot-long enclosed terminal.

Chicago and North Western Station and train sheds looking south in 1961. Photo via Chicago & North Western Railway Archives.

The head building’s upper level catered to inter-city passengers and featured an array of amenities such as dressing rooms, baths, and medical facilities. The waiting room’s crowning glory was its striking 84-foot-tall barrel-vaulted ceiling, adorned with intricate plasterwork and elegant chandeliers. The ground floor provided a separate waiting area for daily commuters, connecting them to popular destinations like Milwaukee and Madison, Wisconsin.

The Era of the 400 Series Trains and the Unconventional Left-Handed Train Station

Between 1935 and 1963, the iconic 400 Series trains operated from the Chicago and North Western Station to St. Paul, Minnesota. Renowned for providing comfort and extraordinary speeds, the 400 made headlines in the late 1930s when it reached an impressive 108 miles per hour en route to Minnesota. Despite utilizing existing equipment, the 400 successfully rivaled the velocities of the Burlington’s Zephyr and Milwaukee Road’s Hiawatha.

Chicago and North Western Station from above in 1964. Photo by David Daruszka

Chicago and North Western Station interior via David Daruska / Towns and Nature

A unique feature of the Chicago and North Western Station was its reputation as the “left-handed train station.” This peculiarity originated during its single-track days when the second track was introduced on the side opposite the station. As a result, the inbound track remained the closest to the platform. This practice persisted when the new station was constructed, requiring passengers to board on the atypical side compared to other rail lines.

Chicago and North Western Station in 1960. Model by Jack Crawford / Rebar Radar

Chicago and North Western Station in 1983, one year prior to demolition. Model by Jack Crawford / Rebar Radar

View of where Chicago and North Western Station once stood in 2023, 39 years after demolition. Model by Jack Crawford / Rebar Radar

View of where Chicago and North Western Station once stood in 2033, 49 years after demolition. Model by Jack Crawford / Rebar Radar

In its heyday, the station also housed a renowned Fred Harvey restaurant, which offered high-quality dining to travelers and became a beloved destination for locals and visitors alike.

Chicago and North Western Station prior to 1955 via Jeff Lewis / Towns and Nature

The Loss of a Rail Legend

The Chicago and North Western Station met its demise in 1984, demolished to pave the way for the much glassier Citicorp Center Tower. In its place, the Ogilvie Transportation Center now operates, named in memory of former Governor Richard B. Ogilvie.

Chicago and North Western Station in 1960. Model by Jack Crawford / Rebar Radar

Chicago and North Western Station in 1983, one year prior to demolition. Model by Jack Crawford / Rebar Radar

View of where Chicago and North Western Station once stood in 2023, 39 years after demolition. Model by Jack Crawford / Rebar Radar

View of where Chicago and North Western Station once stood in 2033, 49 years after demolition. Model by Jack Crawford / Rebar Radar

While the Chicago and North Western Station no longer stands, its rich history and architectural significance remain documented in the annals of Chicago’s past. As a “Lost Legend,” the station exemplifies the dynamic nature of urban landscapes and highlights the value of safeguarding our architectural heritage.

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews

Great historical overview of a time when travel by rail was the norm and grand stations were built to serve the masses in style. We are proud that we are part of preserving the classic design of Frost and Granger at the former Powerhouse located just south of the station at 211 N. Clinton where our offices are located. Thanks to YIMBY and the Lost Legends series for reminding us of our past. Mike Drew, Structured Development

Train travel needs to become fashionable and convenient again. Chicago needs to restore inter city travel and improve CTA and METRA service .

Absolutely gorgeous, just gorgeous

I greatly enjoy reading about these Lost Legends. Chicago has such a beautiful architectural past.

As a current resident, I’d love to see the city preserve what we have left and upgrade the quality of our existing rail services (CTA, Metra, Amtrak). According to this article, it seems that travel by rail was a much better experience (faster and more amenities) than it is today. I realize that fewer people travel by train today, but even if we have fewer stations and trains, we should still have world class amenities and fast, safe train service for passengers.

Fewer people travel by train primarily because we destroyed non-car-based transportation systems in the 50s, 60s and onward. A good portion of the rest of the world has much more transportation choice than we do today, and this choice has been effective at limiting our great city from becoming an even more vibrant version of itself. This is even painfully obvious in NYC…it’s so far behind its global peer cities in train travel.

I enjoy finding the small bits that remain today, in the French Market and the north platform entrances. I came of age as the Ogilvie was being constructed and I remember well the utter confusion of temporary platforms, stairways, and pedestrian bridges. It was a terrifying lesson to this farm kid about wayfinding in the city!

I am very much not a part of the whole architecture revival movement, and like increasing density, but I can’t help but think where did we go wrong?

One world, cars.

*word

The 1848 G&CU depot was not at Wells Street, but west of the river on Carrol and West Water. Wells street was built several years later. After the C&NW was formed in 1864 the company used 3 depots for many years. While the brick Wells Street Depot burned in 1871, the frame G&CU depot survived until 1881, when the new Wells Street Deport by W.W. Boyington was built.

The 1911 building was built to comply with municipal ordinances requiring track elevation. The main Waiting Room’s ceiling was not plaster, but Guasivino Thin Tile Vaulting with Terracotta trim. The ground floor of the headhouse was not used by commuters–they require little space. It was used ticket ticketing, baggage claim, etc.

Fred Harvey had no restaurant. Albert Pick & Co. was primary concessionaire.