YIMBY recently spoke with Larry Booth, a founding member of the Chicago Seven and principal at Booth Hansen, about his latest book, “Modern Beyond Style and the Pursuit of Beauty.” With a career spanning decades, Booth has significantly influenced both Chicago’s architecture and the wider field. In the following interview, he discusses insights from his new book and reflects on key milestones and challenges that have shaped his work.

Drawings by Larry Booth via “Modern Beyond Style and the Pursuit of Beauty”

1 – Craftsmanship at the Core

Crawford: Thank you Larry for taking the time to chat today. I'm eager to delve into your career, your educational background, and the impact your work has had on Chicago and the broader architectural community. Booth: Sounds good. To give some context, the reason I wrote the book was to really understand what I had accomplished over the years. This process started because someone asked me what kind of architecture I practice, forcing me to articulate that in a brief elevator pitch. Crawford: Interesting. So the concept of the elevator pitch was the catalyst for the book? Booth: Yes, that’s correct. It took about three years and several revisions to truly distill my thoughts. I'm not as literal-minded as some, so it took some time to figure out exactly what I was thinking. Crawford: Going into this process, did you already have a clear ethos for how you approach architecture? Or did this turn out to be more of a period of self-discovery where you reflected on the meaning behind your work? Booth: The term "discovery" is key here. From the beginning, even before we opened our first office, it was always about discovery. We never had a preconception or stylistic bias. Initially, we did a lot of remodeling in Chicago neighborhoods where housing was becoming attractive due to its affordability. With each project, like transforming an 1890 townhouse into a modern living space, we had to wrestle with existing structures. So, each project became an exploration rather than applying a predetermined idea. Crawford: Do you feel that starting in the world of renovations grounded you in architectural history and allowed you to expand your approach? Booth: One thing I learned was a great respect for the people who built these old buildings. They were very smart, both in their use of materials and detailing. These buildings have lasted 100 years, so they're durable and still attractive to buyers. Crawford: Did your early work focus on the level of craftsmanship in these old buildings? Were there a lot of repairs needed? Booth: My first commission was a kitchen in a Louis Sullivan townhouse. That project did have a sense of dealing with existing conditions, and it was good training for looking at possibilities in any given condition. Crawford: Was there a defining project from that period in your early career? Booth: My first standout project was the Barglow House near the University of Chicago. It became a record house and gave us some notoriety. We started the firm in 1966, and that project was finished in 1969. Building a practice takes time.

Barglow House (1969). Photo by Philip Turner

Barglow House (1969). Photo by Jack Crawford

Booth Hansen’s Compass Points

2 – Compass Points

Crawford: Can you elaborate more on the term "compass points" and how they drive your approach to projects? Booth: The compass points help us navigate each stage of the project. One of the key points is "sweat the details," which starts at the beginning with the little details that may become more important later on. Another point is "simplify for beauty." Crawford: Is "simplify for beauty" aimed at how buildings are interpreted psychologically? Booth: Each stage of the design and construction process emphasizes different compass points. These are not rules but guides that help us know where we are in the project. One of the points is "dialogue reveals ideas," which emphasizes the importance of talking with clients to stimulate design thinking. Crawford: Do you create user personas to understand the specific needs of the people who will be using the buildings you design? Booth: Yes, empathy for the users is crucial. We aim to break down any biases and focus on the realities in front of us. The user knows more about what they're building than we do, so their input is invaluable. Crawford: It seems like direct communication with the client is a significant part of your approach. Booth: Absolutely, a lot of our process is done to get away from biases that have been instilled in us. Direct communication helps us focus on the realities and the needs of the client.

Magnuson House (1974). Photo by Christian Staub

Magnuson House (1974). Photo by Christian Staub

Drawings by Larry Booth via “Modern Beyond Style and the Pursuit of Beauty”

3 – Science, Aesthetics, and Human Values

Crawford: You were part of the Chicago Seven, a group that moved away from predefined, rigid architectural rules toward a more humanistic era. Can you elaborate on what led you to be a part of this transition? Booth: I was influenced by Mies van der Rohe, who was a great architect. However, his one-size-fits-all approach made for a lot of boring buildings. Architects who followed him often produced even more lackluster designs. That prompted me to ask, "How do you escape this trap?" Chicago has a rich architectural history, and at the time, in the 60s and 70s, we were rediscovering the value of architects like Daniel Burnham. So, I sought to bring a kind of energy and soul into architecture. Crawford: You mentioned the neuroscience of aesthetics. How does this play into your architectural philosophy? Booth: According to research, the human eye processes visual information based on verticality and horizontality. This explains why we can universally agree on what a perfect square or rectangle looks like. This is a sort of universal form, unrelated to function, that informs our sense of beauty. This idea guides my approach, emphasizing that form does not necessarily follow function. Crawford: So, you think the form and function are separate domains? Booth: Absolutely. The idea that once you satisfy the client's needs, you've done enough—this is a low bar. Many buildings could be better. It's not about personal preference; architecture is more of a science. Crawford: Do you think there's a lack of dialogue with the client that leads to this? Booth: It's a range of factors. The prevalent notion that beauty is arbitrary undermines the value of aesthetics in architecture. Crawford: Can humanism in designs enhance their perceived beauty? Booth: Beauty is more about careful proportioning, like harmonies in music. You can't necessarily translate functional satisfaction into beauty. Crawford: What's your take on architects like Frank Gehry, whose work is almost sculptural? Booth: Frank Gehry is good because he understands how to build. His sculptural elements usually come after solving the basic problems of a structure. But it's a risky endeavor; architecture should not primarily be an art form to express individual personality. Crawford: So you see architecture as more of a science than an art? Booth: Precisely. If you want to be an artist and express your personality, then don't make the practice of architecture into a studio art form.

Glassberg House (2012). Photo by Bruce Van Inwegen

Glassberg House (2012). Photo by Bruce Van Inwegen

New Buffalo Residence (2015). Photo by Steve Hall

New Buffalo Residence (2015). Photo by Steve Hall

4 – Quiet Architecture

Crawford: You've also worked with architects like Jeanne Gang and David Woodhouse. How have these collaborations influenced you? Booth: We had a very stimulating work relationship for several years. We both enjoy critiquing and brainstorming ideas. Jeanne, for instance, is constantly exploring and building. Crawford: Do you both share a similar architectural philosophy of breaking the norm? Booth: Well, I'm more drawn to the Italian Renaissance, whereas she leans toward quieter, more contemporary architecture. Crawford: Is this idea of "quiet architecture" something you apply across your projects? Booth: Yes, especially in residential settings. For example, one client believed our design added years to her husband's life due to its calming influence, which we achieved by bringing in the horizon of Lake Michigan. Crawford: Interesting. And how does your philosophy adapt for urban settings, where nature is scarce? Booth: Chicago’s motto, "Urbs in Horto" or "City in a Garden," is always a guiding principle. The aim is to integrate nature wherever possible, even in compact city homes. Crawford: Your designs are said to create a "richness of spirit through shared memory." Does that relate to the idea of co-experiencing nature? Booth: Absolutely. If you can recreate that experience of being in nature, it adds another layer of connection.

61 East Banks Street Condominiums (2019). Photo by Troy Walsh

Joffrey Tower (2005). Photo by Michelle Litvin

5 – Current Trends

Crawford: Do you see any current architectural trends in Chicago that are exciting? Booth: There’s no single dominant style right now. The focus has largely shifted toward sustainability and reducing our carbon footprint. Crawford: Speaking of sustainability and technology, do you see automation affecting the architectural process soon? Booth: Technological advancements, especially in glass, are noteworthy. But they also raise questions about energy efficiency and environmental impact. Crawford: You've worked with a wide range of materials. Is there one you find particularly intriguing? Booth: Glass-reinforced concrete was fascinating to work with, particularly in the case of Joffrey Tower at State and Randolph.

Palmolive Residences – renovation (2008). Photo by Jack Crawford

Palmolive Residences – renovation (2008). Photo by Steve Hall

Palmolive Residences – renovation (2008). Photo by Steve Hall

6 – A Balance of Old and New

Crawford: Looking back on your career, is there a project that stands out as encapsulating your creative philosophy? Booth: Oddly, I recently drove past some buildings we've done and felt detached. It's less about reflecting on past works and more about what’s next. Crawford: So the focus is always on the next challenge? Booth: Precisely. It's about what's going on now and what lies ahead. Crawford: Do you have a vision for how the firm might adapt to the changing landscape of architecture? Is it more of a case-by-case adaptation rather than a planned evolution? Booth: You can't control the future, so planning for it is tricky. However, you can teach people how to think clearly. That's one of the reasons I wrote my book—to clarify our firm's approach. We're fine-tuning our checklist and approach to get the best results without trying to predetermine them. The attitude and thought process are what matter. My experience teaching engineering students at Northwestern has been valuable. We only spend four hours a week in architectural studio, but the learning is immense. Crawford: As you educate the next generation of architects, are there key principles you emphasize? Booth: Our compass points are meant to guide people. The idea of "innovation echoes tradition" is crucial. We strive for innovation but also respect the practicalities of tradition. For example, consider Calabria's farmhouses—they blend beauty and practicality, a balance we aim for. Crawford: Are there any projects where this balance between tradition and modernity is evident? Booth: The Shore Acres Clubhouse project from the mid-80s exemplifies this. David Adler had initially designed it, and his work was exquisite. When his clubhouse burned down, I was brought in. Despite my modernist leanings, I respected the affection the members had for the original design. The new clubhouse had to accommodate over 200 members, unlike the original built for 60. The end result blends modern planning with traditional detailing, capturing the appropriate spirit of the design. Crawford: There's a shared psychological element in architecture, isn't there? Booth: When we opened the building, they had a party. Everyone thought it was exactly the way it used to be, particularly the living room. We duplicated it from pictures because we didn't have drawings. That's where the concept of 'spirit' came into play. It started with systematic approaches, followed by performance and then spirit. Over time, these aspects melded together. Crawford: Is it like a balancing act? Do you have to balance these different elements, much like cooking a dish? Booth: We're like chefs. People experience food and buildings in different ways, and that experience is what they remember.

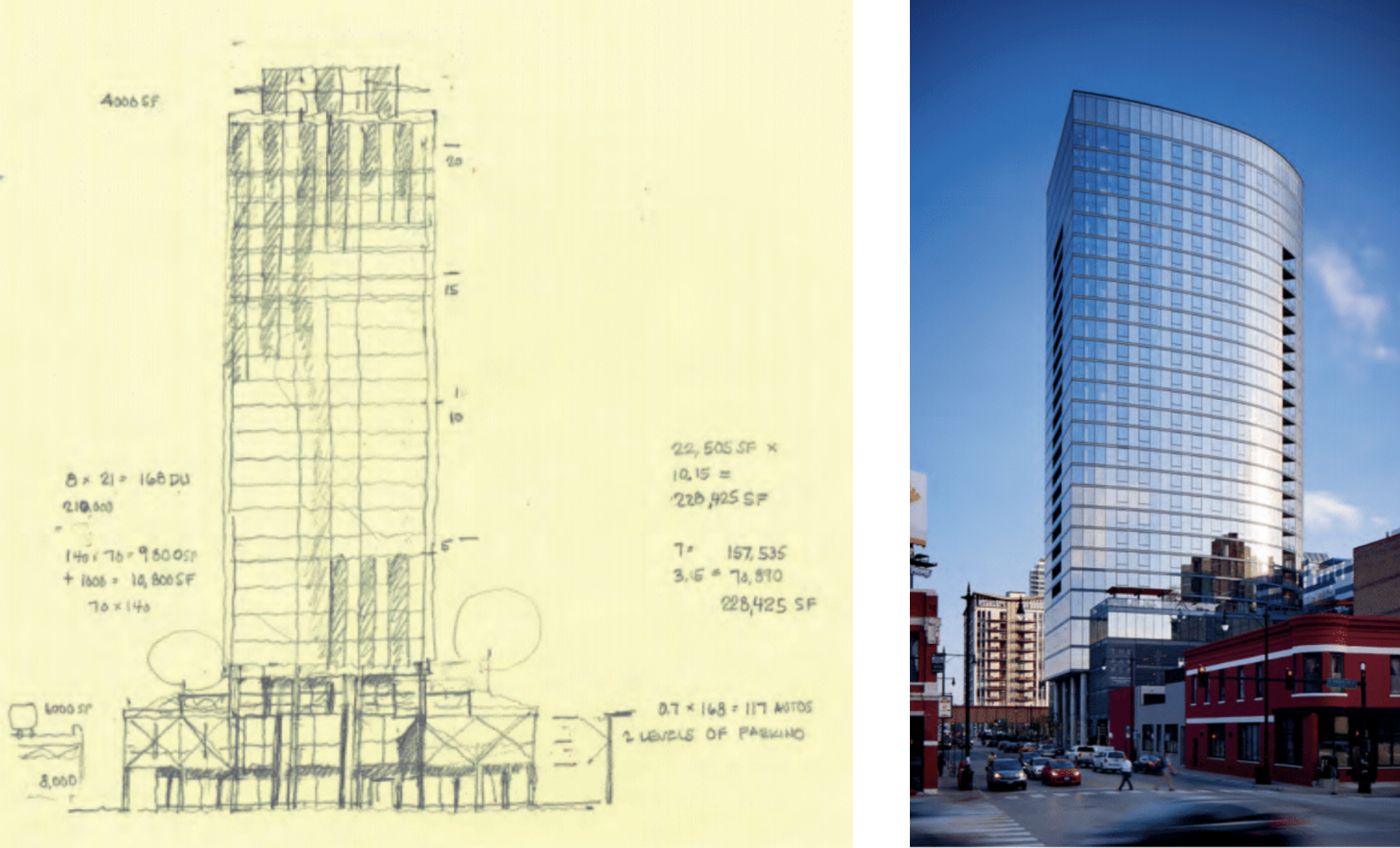

Cleveland Court (1997). Drawing (left) by Booth Hansen; photo (right) by Bruce Van Inwegen

The Parker (2016). Drawing (left) by Booth Hansen; photo (right) by Dave Burk

7 – Design Approaches

Crawford: Beyond the compass points you discussed earlier, have you found other ways to codify your methodologies? Booth: Design ability is more scientific than intuitive. Approaching the practice, especially with systems buildings, is more scientific. You have to understand the goals and issues. We always try to get the client to outline what they want. Crawford: Is outlining the goals usually the first step, or does it depend on who the client is? Booth: Some clients are good at that, while others are not. Either way, we need to know what they want to deliver the right results. Crawford: Do you ever help them figure out what they want? Booth: David Adler, an architect, had an interesting approach. He collected postcards from all over Europe and gave them to clients at the start of a project, asking them to pick what they liked. It's a way to directly address what the building should look like. Crawford: That's an interesting exercise—very interactive. Booth: It gets right to the issue: what does this thing look like? Crawford: Do you employ any unique or interactive exercises for clients to help them determine what they want in a building? Is the focus initially on functionality or aesthetics? Booth: One of the most successful exercises we use involves 3x5 cards. We ask clients to jot down ideas for each room or space on individual cards. For instance, if we're considering the kitchen, clients will list out all the features they desire. This exercise is particularly effective for residential projects. Once we have these cards, we create preliminary designs for each space based on the client's input. Finally, we present the client with three distinct ways to assemble the spaces. Crawford: So from that point, you start refining the design? Booth: Exactly. The goal is to create a building the client will love. Crawford: It's evident that a dialogue between you and the client starts quite early in your process, and it seems to have positive downstream effects. Booth: Dialogue is crucial. In fact, it makes the entire process more enjoyable. We recently worked on a synagogue, and the clients were truly engaged in the design conversations. But what really matters is not defending a design but letting it stand on its own. Crawford: How do you manage the overwhelming number of considerations for each project? How do you narrow it down to a focused vision? Booth: Designing three different building options helps remove possessiveness from the process. Each new project is an opportunity for exploration, and I try to avoid any preconceptions. If a design can't stand on its own merits, it's not worth defending. Crawford: That's an interesting perspective. In architecture school, the emphasis often seems to be on defending your designs, but what you're saying makes sense. The design should speak for itself. Booth: Exactly. Schools may teach architects to have strong and defensible ideas, but I go in the opposite direction. The design should connect with the client and stand on its own. If it can't do that, it's not worth pursuing. Crawford: Your humanistic approach allows the buildings to speak for themselves, and that seems self-evident in your work. Booth: That's the aim. Each design should meet the unique needs and desires of the client, without needing a defense.

1400 W Monroe. Photo by Angie McDonald

1400 W Monroe. Photo by Angie McDonald

The Sally at 1135 W Winona Street (2023). Photo by Jack Crawford

The Sally at 1135 W Winona Street (2023). Photo by Jack Crawford

8 – Beauty, Truth, and Goodness

Crawford: As we wrap up this conversation, I'd like to know what you want your lasting impact to be in the field of architecture. Booth: I believe that beauty, along with truth and goodness, are the three anchors of civilization. In modern times, architecture has somewhat lost touch with the concept of beauty. I think it needs to be reintroduced, better understood, and appreciated. Buildings can be beautiful; we just have to work at it. Crawford: On a larger scale, how important do you think beauty is in architecture? How would you respond to someone who focuses solely on utility? Booth: There's greater satisfaction in being in a space that's not just functional but also aesthetically pleasing. There's nothing wrong with seeking comfort and satisfaction. Crawford: So, do you see us reconnecting with earlier principles of architecture, before the modernist movement perhaps? Booth: There's a lot of reevaluation of modernism happening now. The removal of ornamentation in favor of mechanical systems is something we need to look at. It comes down to what can be afforded within a budget, but ideally, both elements can coexist. Crawford: It sounds like there's a balance to strike between several factors. Booth: Absolutely, it's about finding that balance. Crawford: Your work certainly seems to be pushing the boundaries in combining beauty and function. As we see sustainable trends gaining traction, your approach offers an exciting model for what architecture could be. I'm eager to see what your firm will tackle next. Booth: That sounds excellent. Crawford: Wonderful. It's been really insightful talking to you. Thank you for your time, and I look forward to following up soon. Booth: It's been a pleasure. Thank you, Jack.

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews

I liked to read this interview between you and Larry, Jack. I feel grounded when I look at a Booth Hansen building, not excited, and I love that about their work; I feel calm when in the presence of their buildings.

Oh wow, I hadn’t heard of him which is a strange blind spot for me, but damn, I love every single one of his buildings! Awesome interview!

We just purchased a Larry Booth home in Nw Indiana. We love it

We live in an Evanston home with a fantastic 1976 Larry Booth addition. Everyone loves our house!