Chicago’s Central Station, once a hub of vibrant activity, represents a significant chapter in American railway history. Constructed in 1893, the station was designed by esteemed architect Bradford L. Gilbert to accommodate the traffic demands of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Located near Roosevelt Road and Michigan Avenue, the station’s strategic position was instrumental for moving people and goods within the city and beyond. Notably, there was another dismantled passenger station known as Grand Central Station, which was highlighted in a previous Lost Legends article.

Photo by Jack Boucher – Historic American Buildings Survey

Architectural Features

Central Station was an epitome of the Romanesque Revival architectural style. Its exterior boasted a clock tower, emphasizing the station’s integral role in daily life. Inside, the grand waiting room showcased marble columns, intricate plasterwork, and a magnificent skylight. The design was as efficient as it was stunning, catering to the burgeoning needs of train travel during that period.

Ticketing area at Central Station. By railfan 44 – https://www.flickr.com/photos/129679309@N05/23728641439/

Impact on the City and the Rail Network

Central Station significantly influenced Chicago’s evolution, connecting the city nationally and underpinning economic and cultural growth. An integral component of Chicago’s broader rail system, the Illinois Central Railroad, the station stood as one of the most comprehensive in the U.S. Serving as a pivotal junction, Central Station connected the city to multiple destinations.

Demolition of Central Station. Photo by J.R. Schmidt

Demolition and the End of an Era

Despite its architectural and historical importance, Central Station could not withstand the shift in American transportation preferences. With the increasing popularity of cars and airplanes, the allure of rail travel diminished. By the mid-20th century, the station’s relevance dwindled. Passenger operations ceased in 1972, leading to its demolition between 1974 and 1976. This event symbolized a profound transformation in Chicago and the nation’s transportation scene.

What Stands Today

Today, the former Central Station site is home to a mixed-use development named Central Station, featuring residential, commercial, and recreational spaces. Although the original structure no longer exists, its legacy endures in Chicago’s history and in the recollections of those who once walked its corridors.

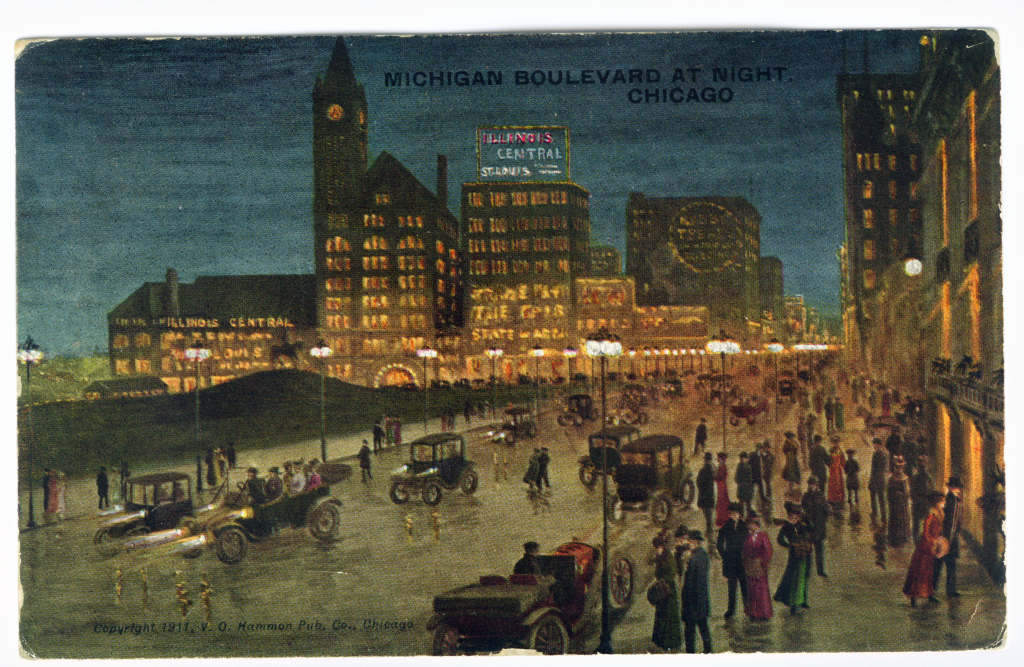

1911 postcard depicting Central Station. Photo by V.O. Harmon Pub. Co.

Chicago’s Central Station was not just a transportation center; it encapsulated the ambitions, dynamism, and innovation of a rapidly growing city. Its existence symbolized not just Chicago’s expansion but also the significance of railway systems in molding the nation’s economic and cultural identity. The station’s demolition mirrors broader societal shifts towards different transportation modes, marking a watershed moment in both the city’s and the nation’s chronicles. Nonetheless, Central Station’s memory remains a lasting testament to a bygone era and continues to shape our comprehension of transportation’s evolving role in urban growth and nationwide linkage.

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews

Such interesting stuff.

I hope this series continues for a long time.

So sorry to see what once was Chicago lost to so-call modernism.

Central Station, also known as the Illinois Central Station (“IC”), or main IC terminal at Roosevelt Road (verses the IC/South Shore Line, Randolph Street Station, now Millenium Station), was also a principal port of entry for the Great Migration, for many African American’s moving from the rural South to Chicago and many cities of the Northern US in the early decades of the 20th century. It was also the place where Emmett Till’s casket was received in Chicago, by his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley and their family.

The building was never thought to be architecturally significant, and certainly not as important as many of the other train terminals (Grand Central, Dearborn Station, North- Western Terminal, Union Station, LaSalle Street Station or others), but yet very historically and culturally important in many ways.

I remember watching the demolition of the building and also the “Dowie Building” adjacent to the IC Station. The Dowie Building was said to be the largest structure ever moved from one site to another. Anyway, they slowly demolished the IC station and the last portion to be demolished was the tall clock tower, which appeared to defy proudly the demolition of the station. Of course that was now a half-a-century ago and so much has changed and the South Loop has now become a destination, where it was once a sort of “no-man’s land,” and kind of an empty area, forgotten by time.

Yes. It was known as the “Black Ellis Island” during the Great Migration.

Progress is not always progressive

The Colombian Exposition in 1893 was only part of the reason for Central Station’s construction. Its predecessor, Great Central Station, had burnt in 1871 and due to disagreements between its owners, had never been rebuilt. For nearly 22 years trains operated from Great Central (north of Randolph Street) from within its burnt walls.

Central’s waiting room was above track level and passengers had to go upstairs to go down to their train. Louis Sullivan excoriated this design in his Kindergarten Chats. He was really mad that he didn’t get the commission as his brother Albert was the Illinois Central Railroad’s Chicago Superintendent. The waiting room did not have a skylight per se. It featured a huge barrel vault with glass curtain walls at each end. To the east this looked out over Lake Michigan whose shore as then only feet away. The poly-chrome vault was concealed by a drop ceiling about 1940.

In later years the depot looked like a jumble of buildings and it was. It incorporated the headquarters offices of the IC and, as the railroad grew, additions were slapped-on. There was also a “temporary” connection with the 12th Street suburban station, which was neither temporary or on 12th Street. Built on telephone pole stilts with clapboard siding, it really made the entrance area shabby.