The Prentice Women’s Hospital building was once an architecturally iconic structure standing at 333 E Superior Street in the Streeterville neighborhood. In this edition of the “Lost Legends” series, we explore the history of the original Prentice Women’s Hospital building and its cutting-edge care, the vision of its architect, the hospital’s relocation and subsequent demolition of the structure, as well as its present-day replacement.

History

The original Prentice Women’s Hospital building was designed by the acclaimed architect Bertrand Goldberg, who began working on the project in 1971, following the consolidation of Passavant Deaconess Hospital and Wesley Hospital. The medical facility, named after American anthropologist Abra “Abbie” Cantrill Prentice, opened in 1975. As part of Northwestern Memorial Hospital, the hospital focused on women’s health, offering advanced medical care in a nurturing environment. The facility quickly gained a reputation for its commitment to women’s health and its innovative approach, which included specialized care for high-risk pregnancies, comprehensive breast cancer treatment, and state-of-the-art gynecological services.

Prentice Women’s Hospital under construction in 1974 (upper right). Photo by Joe+Jeanette Archie via Wikimedia Commons

Prentice Women’s Hospital under construction in 1974 (highlighted). . Photo by Joe+Jeanette Archie via Wikimedia Commons

Prentice Women’s Hospital. Photo by Uncommon fritillary via Wikimedia Commons

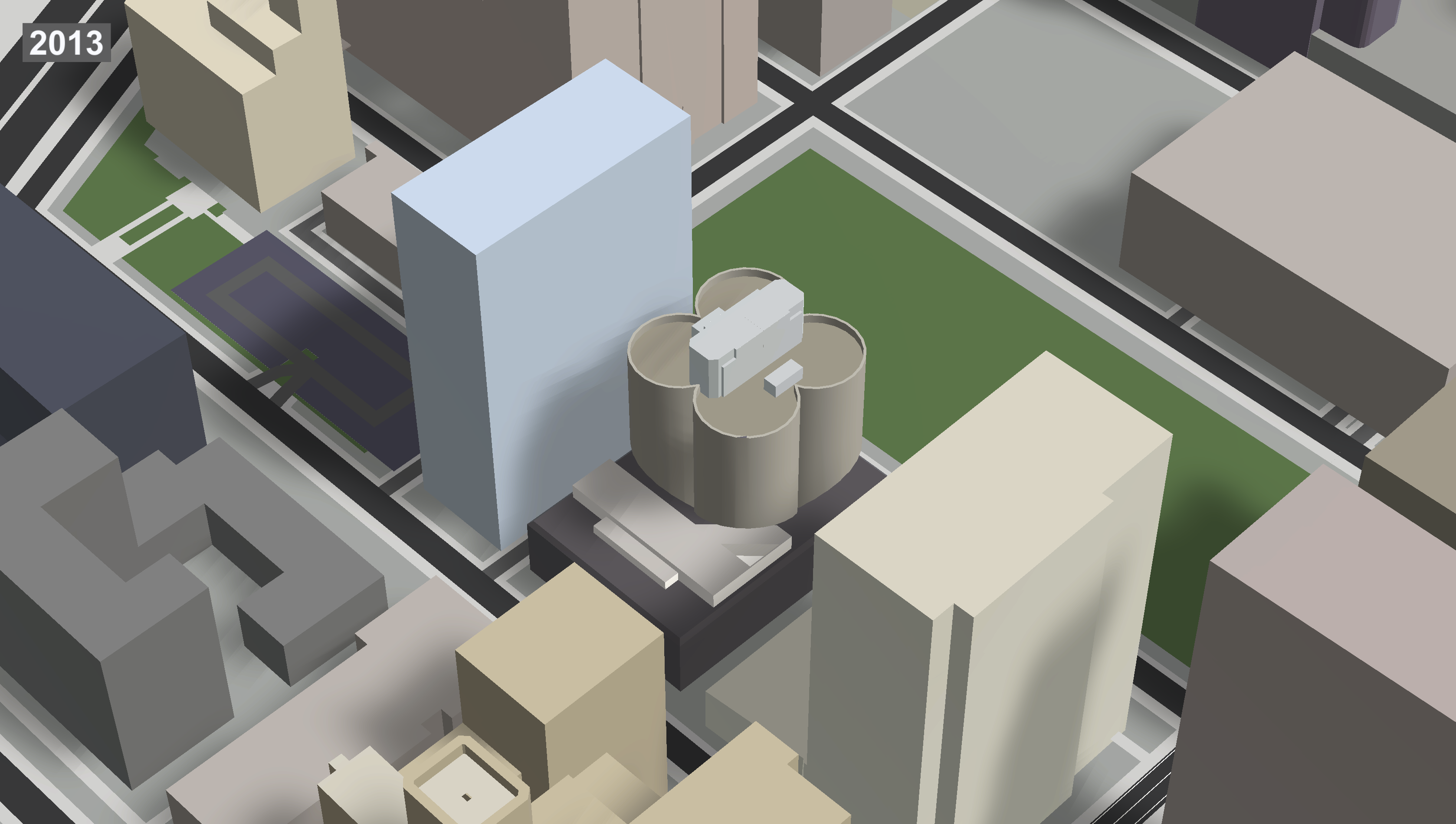

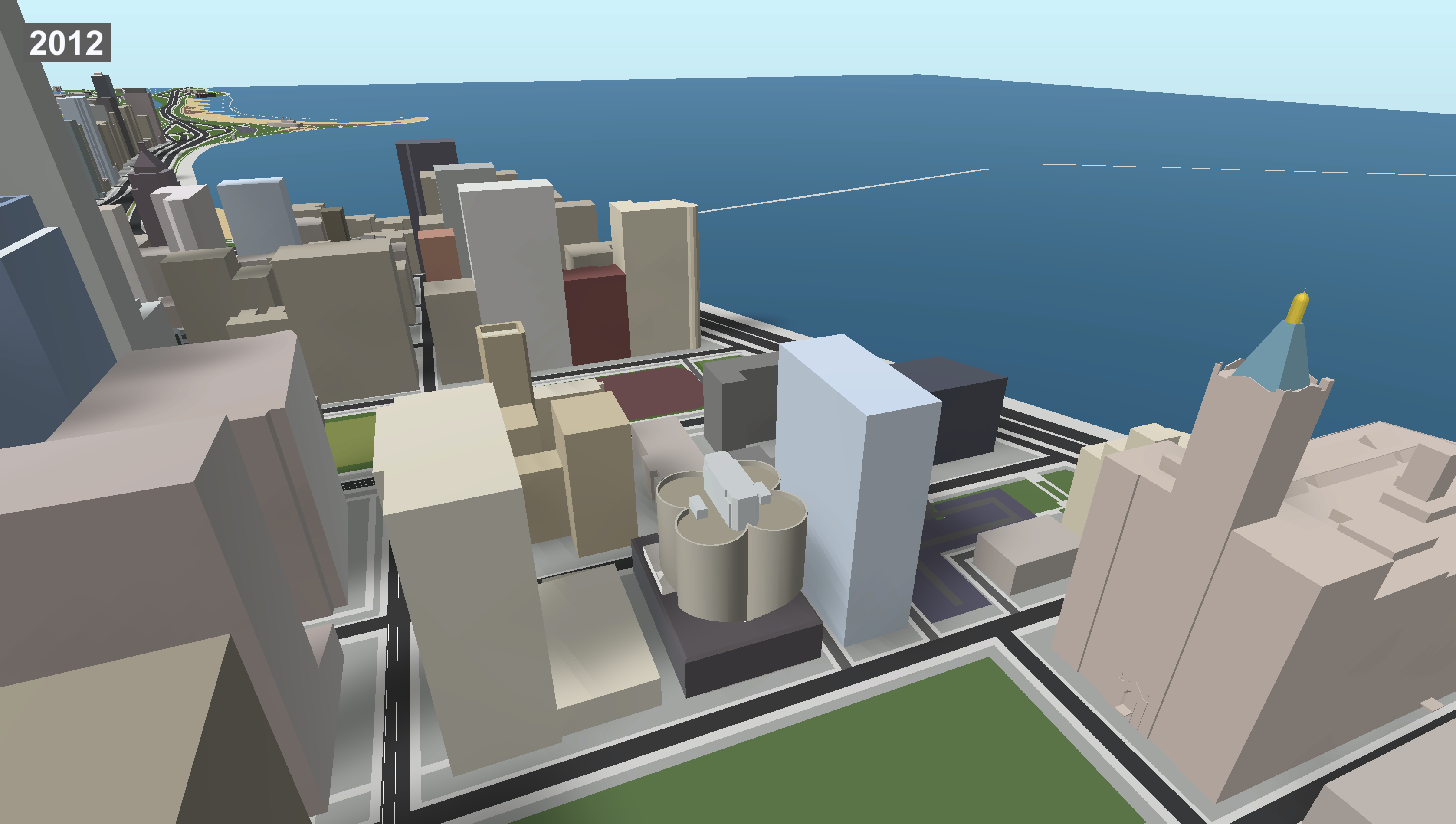

Original Women’s Prentice Hospital. Model by Jack Crawford / Rebar Radar

Architecture

Renowned architect Bertrand Goldberg, known for his inventive and futuristic approach, embraced Brutalist elements in his design for a one-of-a-kind hospital. The building featured a raw concrete exterior and a striking quatrefoil configuration, capturing the essence of the Brutalist movement. This 9-story concrete tower boasted cantilevered oval windows atop a 5-story rectangular base, showcasing a unique blend of form and function.

Women’s Prentice Hospital. Photo by Jim Kuhn

Goldberg’s vision prioritized fostering collaboration among medical professionals while providing a welcoming and comfortable atmosphere for patients and their families. The tower was dedicated to maternity care, with strategically placed nursing stations and patient wards in distinct areas of the structure. This design significantly shortened the distances between medical staff and patients.

Prentice Women’s Hospital. Photo by Umbugbene via Wikimedia Commons

Esteemed structural engineer William F. Baker lauded the hospital for its intricate curvilinear design, recognizing it as unparalleled in the world of architecture. In a pioneering move, Bertrand Goldberg & Associates implemented early computer-aided design techniques for the hospital’s construction. According to an article in Engineer News-Record, the team repurposed software initially used in the aeronautical industry (a similar move to Frank Gehry’s later adoption of aerospace software), devising a 3D mapping method that expedited the design process by several months.

Relocation and Demolition

In 2007, Prentice Women’s Hospital relocated to a new, state-of-the-art facility at 250 East Superior Street, doubling the size of the previous facility at 947,000 square feet and featuring one of the largest Neonatal Intensive Care Units in the country. The transition to the new facility took a few years, leaving the original building vacant in 2011, upon which Northwestern University announced plans to demolish the old building and replace it with a medical research facility.

New Prentice Women’s building at 250 E Superior Street. Photo by JeremyA via Wikimedia Commons

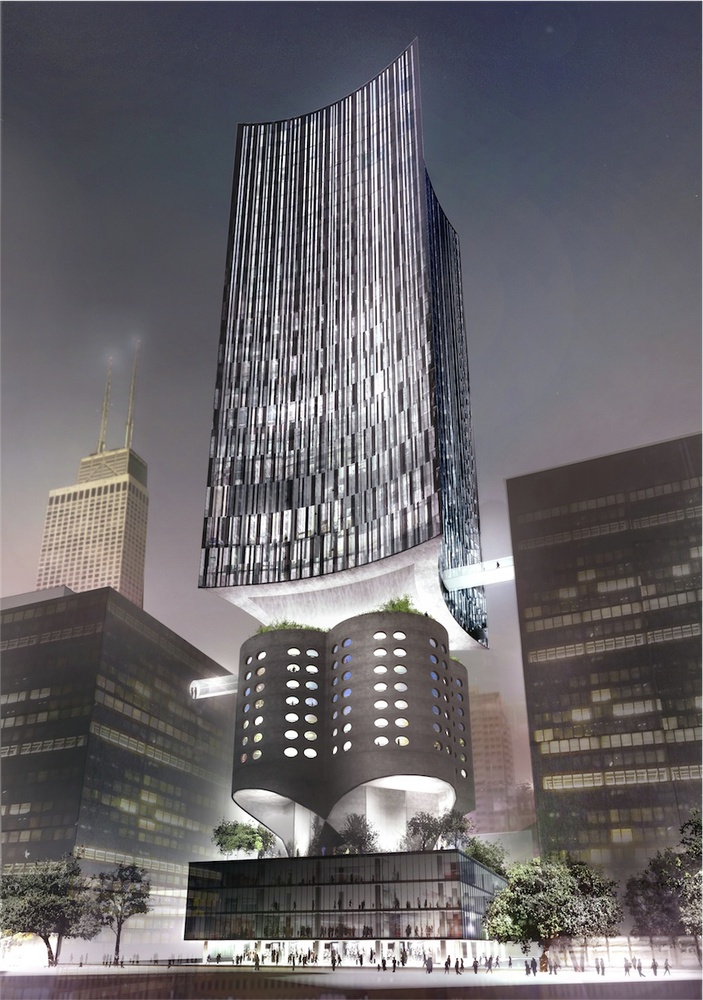

Formerly proposed redevelopment of Prentice Women’s Hospital. Rendering by Studio Gang

There was opposition from preservationists and prominent architects, including at least six Pritzker Prize winners who appealed to Chicago’s “global reputation as a nurturer of bold and innovative architecture.” To address the practical considerations of the site and avoid demolition, Jeanne Gang, in collaboration with architecture critic Michael Kimmelman, had proposed a glassy research skyscraper that would integrate the original concrete structure as its podium. Ultimately, the decision to demolish the original hospital building was made, and demolition commenced in 2013, concluding in 2014.

What’s There Now

The former site of the original Prentice Women’s Hospital building now hosts the Louis A. Simpson and Kimberly K. Querrey Biomedical Research Center. As part of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, this contemporary research facility has just recently announced plans to extend its height from 320 feet to 600 feet as part of its phase 2 expansion. The tower addition will bring the total square footage to 1.2 million square feet, approximately three times the square footage of Goldberg’s original design, for reference.

Louis A. Simpson and Kimberly K. Querrey Biomedical Research Center. Photo by James Steinkamp

Proposed expansion of Louis A. Simpson and Kimberly K. Querrey Biomedical Research Center. Rendering by Perkins & Will

Original Women’s Prentice Hospital. Model by Jack Crawford / Rebar Radar

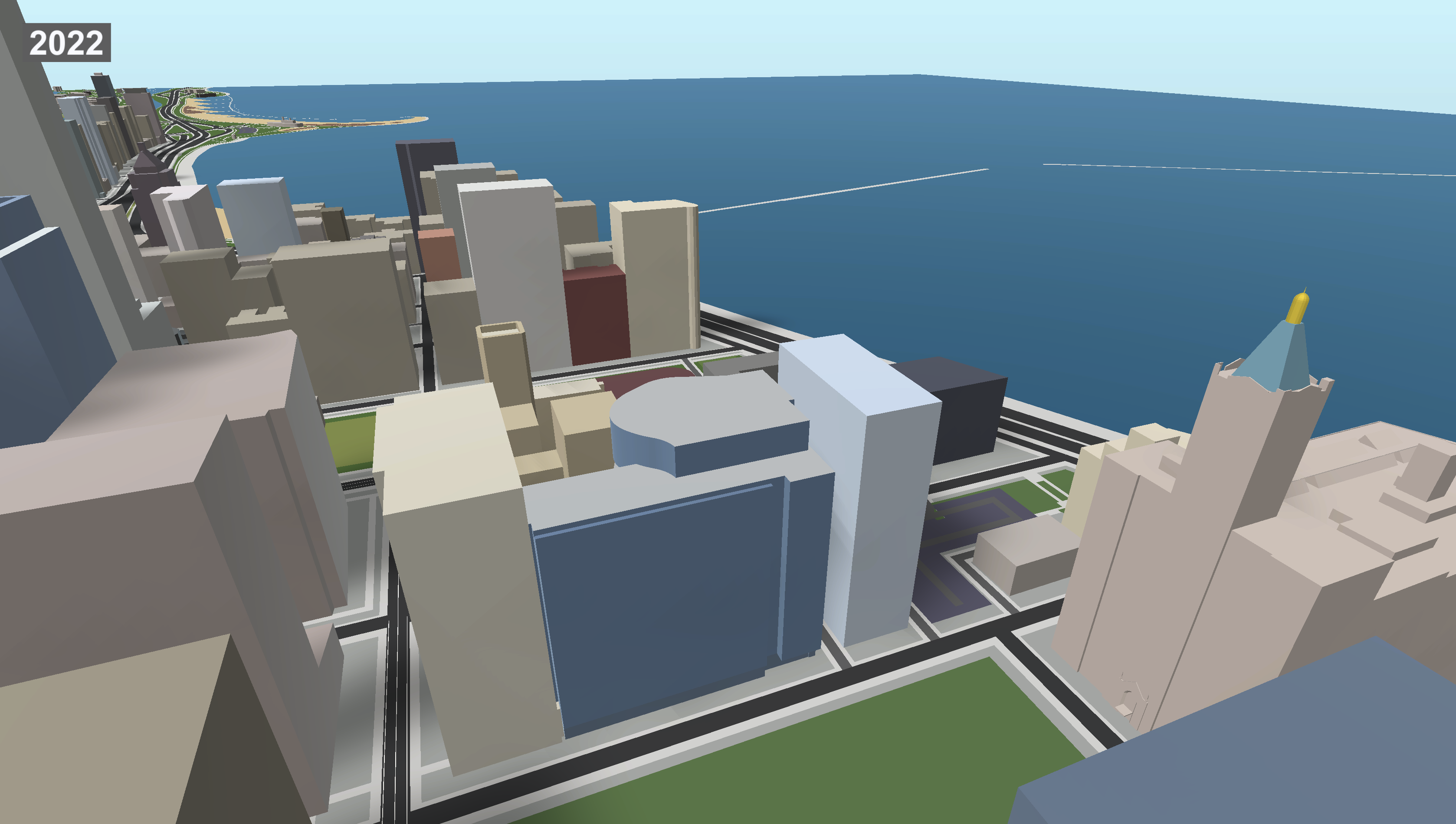

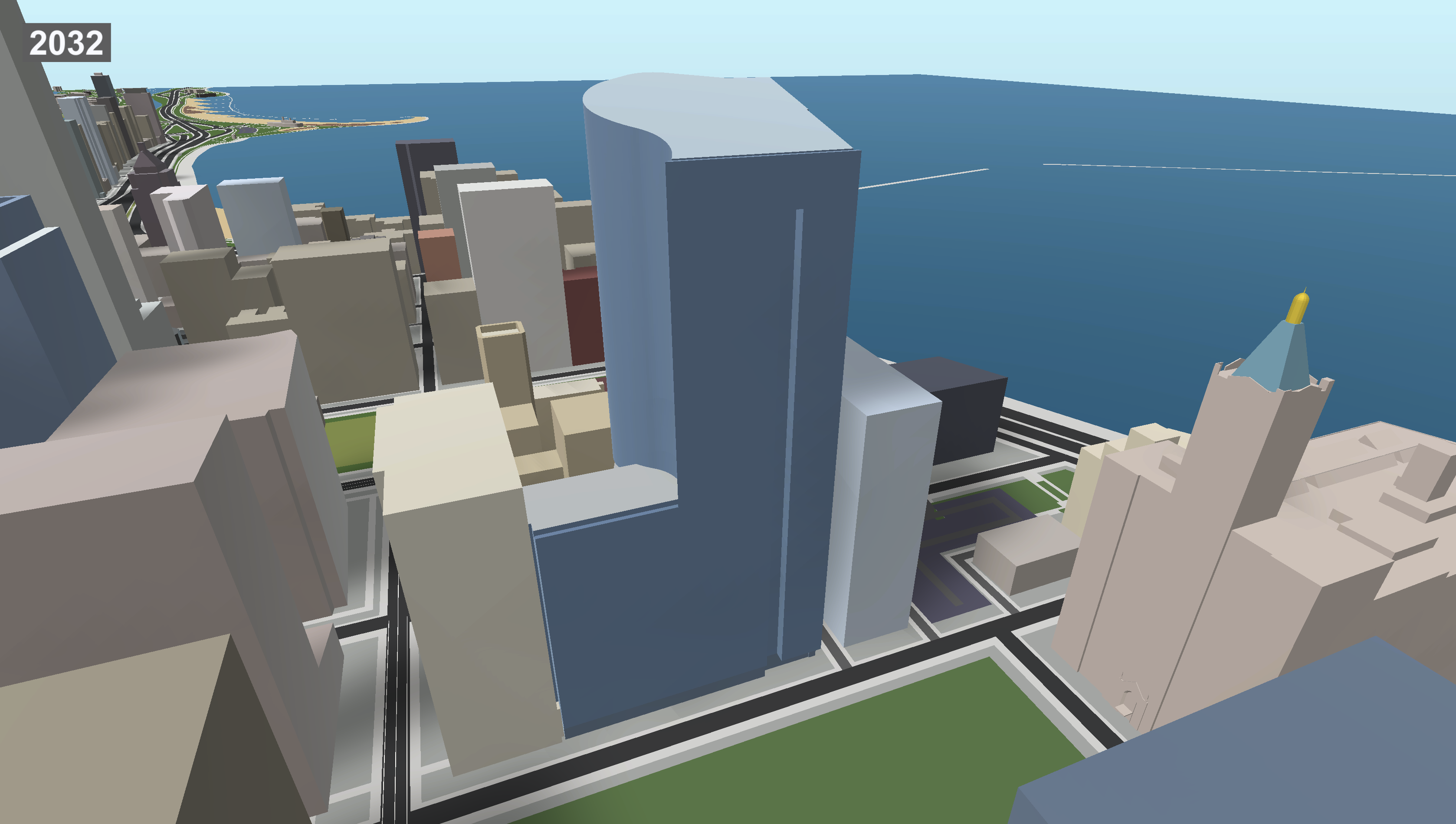

Louis A. Simpson and Kimberly K. Querrey Biomedical Research Center. Model by Jack Crawford / Rebar Radar

Louis A. Simpson and Kimberly K. Querrey Biomedical Research Center expansion. Model by Jack Crawford / Rebar Radar

Like many other installations to our series, the story of the original Prentice Women’s Hospital building again highlights the delicate balance between progress, preservation, and the evolving needs of a city. Stay tuned for more lost legends in future articles.

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews

Uh oh. Marina city construction photograph is mistakenly identified as Prentice. Note tribune tower and Wrigley building east of property.

Hi Paul, Prentice Women’s building is under construction in the upper right. I added a note in the caption

Since there are so many buildings in that photo, I also added an edited version that highlights Prentice

Considering the age of buildings in Europe and even Chicago, Prentice was a colossal failure. To be fair no one anticipated the tech revolution that made the building obsolete in 30 short years, but the fact that it could not be retro-fitted to work for something, like 100s of thousands of other buildings have been and are, is testimony to the fact that it might have been appealing to some, but it remains nonetheless a failure. As a healthcare provider Northwestern and the building itself had an obligation to be more than just architectural.

Very true – the practical aspects that contributed to much of the building’s original appeal were lost as these requirements evolved and tech improved. I agree too that this would have been quite difficult for any kind of adaptive reuse given how it was laid out

My mom worked on a lot of IT throughout this building for the labor units, CT scanning, and general nurse stations. The conditions were abysmal, and there was no practical way to retrofit the tech without some massive gutting, so much there was less being saved than kept. In terms of costs, this hospital, unfortunately, was not made for the 21st century. Plus, the concrete made working with wifi networks tricky; the structure was a mess.

I appreciate architecture of all kinds. But I must admit that I miss this one about as much as I miss the Pizza Hut that used to be at the intersection of North and Western Avenues.

Hideous inside and out.

I can see why they demolished this.

I’m almost always for preservation but this place is not worthy of the title “lost legend”. I don’t want to speak to I’ll of the dead so I’ll say that on a positive note it was interesting and different. But other than that, it was a failure of a building and having spent lots of time there after my niece and nephew were born, it was just a terrible design for a women’s hospital. It was a showpiece only -form did not follow function.

What really bothers me about celebrating (and fighting like hell to preserve) failed buildings like this is that it sets the preservationist cause back in untold ways. To paraphrase The Incredibles, if every old building is special, then no old building is.

Right now we’re fighting an uphill battle to spare the glorious Century and Consumers buildings and I can guarantee the powers that be are saying “eh, no big deal, these preservation people will fight for anything and everything.”. And how can we say they’re wrong when advocates are breathlessly extolling those two beauties in the same press releases that champion saving the decrepit Damen Silos. Silos. Just let that word sink in….Silos….Silos. I’d be delighted if the Silos were repurposed but it’s ridiculous to elevate them into the same discussion.

Please, preservation/landmark advocates: PICK. YOUR. BATTLES. Please!

One last thing. I believe preservation efforts should be focused on structures that couldn’t be duplicated in modern times. Nobody today can or will construct an art deco skyscraper the way they were made in the 20s and 30s. Similarly, ornate Victorian homes (which are getting torn down constantly) will never be replaced with anything close to that level of craftsmaship. But almost anyone could pull out the Prentice Hospital plans out of a drawer and rebuild the structure somewhere else (they won’t because they realize it’s not a good building design – not because things aren’t made that way anymore). Same goes for the Thompson Center, et al.

I would love to see a broader “neo-Art Deco” movement. I think the closest thing to that are aspects of NY towers such as 111 W 57th and some of Miami’s most recent proposals. It would be interesting to see ornate detailing as a whole will make a resurgence as construction technology continues to improve – that could be something we start seeing this decade. I wonder if these advances will also lower costs to restore & preserve historic structures, thus leading to more such projects

Never shouldve been brought down